Philosophy and Foundations of Mathematics Reading Group

Published:

You ask me, which of the philosophers' traits are idiosyncracies? For example: their lack of historical sense, their hatred of becoming, their Egypticism. They think that they show their respect for a subject when they dehistoricize it — when they turn it into a mummy.

This article is about a Philosophy and Foundations of Mathematics Reading Group (PFMRG)I am leading this group. It is hosted on Falafe server on Discord where we have well over a hundred members. The running language is Persian. We meet bi-weekly, and each session will last about two hours (30-45 minutes for presentation, the rest for the Q&A). Most members (mostly PhDs and postdocs in sciences, arts, philosophy, and engineering) have keen interests in philosophical matters, but have little or no previous experience in logic or mathematics. In a way, this is even a better occasion to think the original and the historical, the genuinely histoical, preceding and thereby anticipating all successive history of logic and philosophy of mathematics. The recording of the talks are found in this channel.

which is inaugurated in mid February 2021. The goals of this group and the themes of the presentations are discussed in below. The main characteristics of the reading group are the diversity of topics we shall discuss as well as covering both historical and modern aspects.

Goals & Hopes

The main goal of this reading group is to understand how close the human has come to the point where his machines can do mathematics for him. Some mathematicians, such the Fields medalists Paul Cohen, Tim Gowers, Maxim Kontsevich, and Vladimir Voedodsky have all at some point predicted that computers will be able to out-reason mathematicians in the 21st century. But is that really plausible?

To make any sound judgment on this question, we need to better understand

What is (and what should be regarded as) mathematical progress?

What is (and what should be regarded as) mathematical proof? Do we always need formal proofs to do mathematics? (c.f. theorems vs porisms )

What is the role of human intuition in mathematical reasoning and in mathematical proofs? Where do new ideas in mathematics come from?

What is the role of natural language in mathematics and how different is it from the mathematical languages in which the proofs are written? What are the limits of our mathematical languages compared to our natural language where we reason about mathematics at a meta level? And could these limits be problematic for the computers to do mathematics equally or even better than humans?

What is the machine mathematics? What are automated theorem provers (ATPs) and interactive theorem provers (ITPS) and what are their differences? Can the advances in AI, ML, and neuroscience bridge the gap between ATP+ITP and the human mind when it comes to doing (creating/discovering) interesting new mathematics?

Will we have two mathematics in future: the machine mathematics, and the human mathematics? And how do we, humans, react to such a situation? Will we simply accept the proofs generated by computers which conceivably could not be understood by any human being at all? Will such proofs have the same status as human generated proofs

These are pressing questions and we need to ransack various philosophies and foundations of mathematics that have been thought before us; they give us radically different insights to the questions above and presents us with cast territories of philosophical though. In the first session of our reading group, I will give an introductory talk charting out a basic map of these territories, and establishing some reading resources that get us going.

To put some of the discussions above in context, here is the point of view of the geometrician Bill Thurston regarding the activity of mathematicians:

The product of mathematics is clarity and understanding. Not theorems, by themselves. Is there, for example any real reason that even such famous results as Fermat’s Last Theorem, or the Poincaré conjecture, really matter? Their real importance is not in their specific statements, but their role in challenging our understanding, presenting challenges that led to mathematical developments that increased our understanding.

I think of mathematics as having a large component of psychology, because of its strong dependence on human minds. Dehumanized mathematics would be more like computer code, which is very different. Mathematical ideas, even simple ideas, are often hard to transplant from mind to mind. Mathematical ideas, even simple ideas, are often hard to transplant from mind to mind. There are many ideas in mathematics that may be hard to get, but are easy once you get them. Because of this, mathematical understanding does not expand in a monotone direction.

And he continues

Our understanding frequently deteriorates as well. There are several obvious mechanisms of decay. The experts in a subject retire and die, or simply move on to other subjects and forget. Mathematics is commonly explained and recorded in symbolic and concrete forms that are easy to communicate, rather than in conceptual forms that are easy to understand once communicated. Translation in the direction

conceptual -> concrete and symbolicis much easier than translation in the reverse direction, and symbolic forms often replaces the conceptual forms of understanding. And mathematical conventions and taken-for-granted knowledge change, so older texts may become hard to understand.

Which Philosophies? Which Foundations?

Here is a common sense and self-evident proposal:

What mathematicians think and do should be important for the philosophy of mathematics.

Now, if you are not familiar with the current state of affairs in the philosophy of mathematics in academia, you are for a hard surprise that the proposal above could not be further from the reality of the most of academic activities in philosophy of mathematics. Not in this reading group. We do not want to confine ourselves with the narrow interests of the academic philosophy of mathematics. Here we tend to think of mathematics as a rich network of ideas and their formal embodiements, therefore we will be concerned with the history and development of ideas, concepts, and structures in various branches of mathematics rather than reducing the content of our philosophical interest either to set theory or arithmetic. Therefore, a basic knowledge of mathematics is necessary as a background for the philosophy of mathematics. To get started, perhaps the best introduction is Saunders MacLane’s Mathematics Form and Function.

In particular, we shall try to ask questions such as

When do we call a kind of knowledge mathematical? How does mathematical knowledge grow? What is mathematical progress? What makes some mathematical ideas (or theories) better than others? What is mathematical explanation? etc

I believe in epistemological anarchism, that is, if needed, we have to be receptive to ideas from the most disparate and apparently far-flung domains, even at the price of losing the comfort of our nests. Therefore, in this reading group we will remain open to all ideas and philosophies as long as they are helpful to our goals and hopes discussed in above. May this group be a place for deep learning (and deep unlearning/ unindoctorination) as well as unashamedly free speculations. We will review the main tenets of the following philosophies and foundations of mathematics:

- Constructivism and Intuitionism

- Structuralism

- Formalism

- Fictionalism

- Cognitivism

Upcoming Talks

(2) Introduction to formal logic and formal proofs: From Aristotle’s Prior Analytics to Frege’s Begriffsschrift]: slides

Past Talks

(1) Introduction to Logicism an Frege’s Begriffsschrift, slides, video recording

(0) The initial meeting: Introduction to Kant’s philosophy of mathematics, slides, video recording

(-1) The Roots of Constructivism and Intuitionism in Mathematics - Part II This talk introduced various aspects of intuitionism and its vast differences from the classicial foundation of mathematics (ZFC set theory built on top of the classicial logic). Topics discussed included Brouwer’s writings, BHK interpretation, the principle of excluded middle, the axiom of choice, the continuum, the role of real numbers in classicial and intuionistic mathematics, and the creating mind’s perception of time.

(-2) The Roots of Constructivism and Intuitionism in Mathematics - Part I This talk mostly centered around the role of foundations, and an informal discussion of various foundations of mathematics

Historically what has underlied the growth of our cognitive capacity for generating and understanding new mathematical concepts is basically the recognition of our increasing tolerance for thinking the insane.

Resources and Learning Materials

In below, I list some of the references which I personally found interesting, intriguing, and edifying. Occasionally, we will discuss some of them, but we do not limit ourselves to them.

I have no clue what the philosophy of mathematics is about. Where should I begin?

- At night before sleep:

- LOGICOMIX

- BYRNE’S EUCLID

- Noson S. Yanofsky. The Outer Limits of Reason: What Science, Mathematics, and Logic Cannot Tell Us.

- On Proof and Progress in Mathematics, See also

What’s a mathematician to do? - Saunders MacLane. Mathematics Form and Function

- Robert L. Long. Remarks on the history and philosophy of mathematics. The American Mathematical Monthly, 93(8):609–619, 1986.

- After mid-day coffee:

- Mark Colyvan. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Mathematics

- David Corfield. Towards a Philosophy of Real Mathematics

- Øystein Linnebo. Philosophy of Mathematics

- Penrose, L. S. and Penrose, R. Impossible Objects, a Special Kind of Illusion, 1958. British Journal of Psychology, 49: 31-33.

- Where does mathematics come from?

- The Brain or the Universe – Where Does Math Come From?, A Talk at Kavli Foundation

- Where Mathematics Comes From: How the Embodied Mind Brings Mathematics into Being The authors claim that the mathematics we used to describe as disembodied is in fact embodied. Humans use their bodies, mind, and brain to both form and understand mathematics. All mathematical content resides in embodied ideas and many of the most basic, as well as the most sophisticated, mathematical ideas are metaphorical.

- Hermann Weyl. Mind and nature: Selected writings on philosophy, mathematics and physics. 2002. Edited and with an introduction by Peter Pesic.

- Colin McLarty. The rising sea: Grothendieck on simplicity and generality

- Howard Stein. Logos, Logic, and Logistike. Phillip Kitcher, eds., History and Philosophy of Modern Mathematics. University of Minnesota Press 238–259, 1988.

- While waking up in the morning or chilaxing you can watch:

- Ray Monk. Intro to the Philosophy of Mathematics

- Denis Bonnay. Logic and Mathematics

- Stephen Read. Logical Paradoxes

- Hartry Field. Logic, Normativity, and Rational Revisability, John Locke Lectures in Philosophy. Part I, II, III, IV, V, VI

- Vladimir Voevodsky. What if Current Foundations of Mathematics are Inconsistent?

- Daniel Sutherland. What are Numbers? Philosophy of Mathematics

- Mark van Atten. Brouwer and the Mathematics of the Continuum

- David Corfield. Good mathematics as good narrative

Also, there are a lot of interesting articles on logic, philosophy and foundations of mathematics by John Bell. John was my former mentor. John is a master in tracing back mathematical ideas to their origins in a very rare and particular way which I call “demummification” of mathematical ideas. He has also had a very interesting life which you can read here: Perpetual Motion: The Making of a Mathematical Logician.

Thematized Resources

On Proofs & Proof assistants

Regarding mathematical proofs we shall discuss the following these: (i) Proofs are abstract mathematical objects (inductively-defined data structures such as plain lists, boxed lists, or trees) which are constructed according to the axioms and rules of inference of the logical system. (ii) Proof is not manipulation of meaningless syntactic symbols, as the manipulists, or strict formalists, would have it. The knowledge of truth is gained though proof.

We shall argue against the first thesis and discuss our reasons for favouring the second thesis. Our guiding arguments are essentially those of Corcoran’s:

First, belief can be an obstacle to finding a proof because one of the marks of proof is its ability to resolve doubt. Second, we usually don’t try to prove propositions we don’t believe or at least suspect to be true. Third, the attempt to find proof often leads to doubts we otherwise never would have had. If you have a treasured belief you would hate to be without, do not try to prove it.

However, the second thesis is far from perfect: it does not have the formal force of the first thesis which led to the creation of wonderful mathematical fields such as proof theory and constructive type theory. Also, how does the claim that the knowledge of truth is gained though proof

holds against the Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) whereby the proof convinces the verifier to any high degree of certinty (strictly below 100%)

Some stuff on proofs

- Richard Tieszen. What is a proof?

- Robert L. Constable. Proof Assistants and the Dynamic Nature of Formal Theories

- Herman Geuvers. Proof assistants: History, ideas and future Also, look at these slides

- Hyperproofs

- Proof core. The idea is due to the late philosopher David Charles McCarty. See What are the limits of mathematical explanation? Could proof cores (idea engines that propel formal proofs) be one of the conceptual gaps between mathematical proofs and their formalizations? i.e. does a coding of proofs (w.r.t. a formal language) contains strictly less epistemic data/control the proofs themselves? (e.g. (geometric) proof core of -1. -1 = 1, verus one of its proof code in which integers are coded as pairs of natural numbers.) Proof cores are more easily expressible in higher languages, and they are closer to intuition and mathematical cognition.

- Robert S.Tragesser, Three insufficiently attended to aspects of most mathematical proofs: phenomenological studies

- Scott Viteri, Simon DeDeo, Explosive Proofs of Mathematical Truths

Visual proofs and the role of visual reasoning in mathematics

- SEP, Diagrams

- Peirce, C.S., 1933, Collected Papers, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Barwise, Etchemendy. Visual Information and Valid Reasoning

- Allwein, G. and J. Barwise (eds.), 1996, Logical Reasoning with Diagrams, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barwise, J. and E. Hammer, 1994, “Diagrams and the Concept of a Logical System”, in Gabbay, D. (ed.), What is a Logical System? New York: Oxford University Press.

- Harel, D., 1988, “On Visual Formalisms”, Communications of the ACM, 31(5): 514–530.

- De Toffoli, S., 2017, “Chasing The Diagram – The Use of Visualizations in Algebraic Reasoning”, Review of Symbolic Logic, 10 (1): 158–186.

- De Toffoli, S. and Giardino, V., 2014, “Forms and Roles of Diagrams in Knot Theory”, Erkenntnis, 79 (4): 829–842.

- Halimi, B., 2012, “Diagrams as Sketches”, Synthese, 186(1): 387–409.

- Friedman, M., 2012, “Kant on geometry and spatial intuition”, Synthese, 186: 231–255.

- John Mumma, Marco Panza. Diagrams in mathematics: history and philosophy.

- Roberts, D., 1992, “The Existential Graphs of Charles S. Peirce”, Computer and Math. Applic., (23): 639–663.

Resources For Philosophies/Foundations Of Mathematics

We will get familiar with the following philosophies and foundations of mathematics.

Structuralism

The following papers give a good introduction to the structuralist thinking within simple kinds of structures.

- Richard Dedekind. Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen?

Paul Benacerraf. What numbers could not be. Philosophical Review, 74:47–73, 1965

- Barry Mazur, When is one thing equal to some other thing?, 2007

Structuralism and category theory

A categorical formulation of the structuralist thesis is in

Steve Awodey. “Structure in mathematics and logic: A categorical perspective“. Philosophia Mathematica, 4(3):209–237, 1996

and a follow-up:

Steve Awodey. “An Answer to Hellman’s Question: Does Category Theory Provide a Framework for Mathematical Structuralism“, Philosophia Mathematica, 2004

Feferman, S. “Categorical Foundations and Foundations of Category Theory”, 1977.

Good introductions to category theory are:

- Steve Awodey. Category Theory. OUP. 2006

- Emily Riehl. Category Theory in Context, Dover, 2016

- I. Moerdijk and J. van Oosten. Topos Theory

- Brendan Fong and David I. Spivak. Seven Sketches in Compositionality: An Invitation to Applied Category Theory

- Elaine Landry. Categories for the Working Philosopher. OUP. 2017

On the relationship between the structuralist thesis and the univalent foundation:

- Steve Awodey. Structuralism, Invariance, and Univalence. Philosophia mathematica 22(1):1–11, 2014.

On the relationship between category theory and the set theoretic foundation:

- Michael A. Shulman. Set theory for category theory

Formalism

- Syntax vs semantics: the distinction between the two did not always exist, and it is one of the most fruitful inventions in the history of mathematics.

- Synthetics vs analtics mathematics: what are the differences and similarities?

- Gerhard Heinzmann and Hannes Leitgeb. Formalism, Formalization, Intuition and Understanding in Mathematics: From Informal Practice to Formal Systems and Back Again. Université de Lorraine/CNRS, Nancy 2018.

- Jeremy Avigad. Number theory and elementary arithmetic. Philosophia mathematica, 3(11):257–284, 2003.

Intuitionistic and constructive mathematics and type theory

- SEP articles: Constructive Mathematics, The Development of Intuitionistic Logic, Intuitionism in the Philosophy of Mathematics, Intuitionistic Logic

- Per Martin-Lof. An Intuitionistic Theory of Types. In G.Sambin and Jan.Smith’s Twenty Five Years of Constructive Type Theory. Oxford Logic Guides Clarendon press, Oxford, 1998.

- Per Martin-Lof. Constructive Mathematics and Computer Programming.

- Per Martin-Lof. Mathematics of Infinity.

- Martin-Lof’s collected works

- Errett Bishop. Schizophrenia of Contemporary Mathematics.

- Charles Parsons. The Impredicativity of induction

- Anne Sjerp Troelstra and Dirk van Dalen (1988). Constructivism in Mathematics: An Introduction (two volumes), Amsterdam: North Holland

- Michael Dummett (1977/2000). Elements of Intuitionism (Oxford Logic Guides, 39), Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977; 2nd edition, 2000.

- Ulrik Buchholtz’s course at CMU, Intuitionism and Constructive Mathematics

- Michael Beeson (1985). Foundations of Constructive Mathematics, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

- Johan van Benthem. The information in intuitionistic logic

- nLab. Meaning Explanation

- nLab. Axiom of Choice

- How to implement dependent type theory I II

- nLab. intuitionistic mathematics

- Hirschowitz. Intersection types. Here and here

- Bengt Nordstrom, et al. Programming in Martin-Lof’s Type Theory

- Martín Hötzel Escardó. Introduction to Univalent Foundations of Mathematics with Agda

- Carl Posy. Epistemology, Ontology and the Continuum

- Richard Holton & Huw Price. Ramsey On Saying And Whistling: A Discordant Note

- Ramsey’s Conception of Theories: An Intuitionistic Approach.

- John.L. Bell. Whole and Part in Mathematics

- John.L. Bell. Divergent conceptions of the continuum in 19th and early 20th century mathematics and philosophy

Logic is philosophy’s essence [...] It is the science whereby we are enabled to test reasons.

How To Learn Logic?

Prior Analytics, Aristotle, 350 B.C.E : the first time in history when Logic is scientifically investigated and it is about deductive reasoning, known as syllogism. The Prior Analytics is part of what later Peripatetics called the Organon.

A very good place to learn the basics of modern logic is van Fraassen’s Formal Semantics and Logic. For other standard references have a look at the big books of logic. Also, for extra resources, see here.

Logic, semantics, metamathematics, Papers from 1923 to 1938, by Alfred Tarski, translated by J. H. Woodger, second edition edited and introduced by John Corcoran, Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis 1983

- Logical Paradoxes

- Hartry Field. Saving Truth From Paradox

- Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems

- Smullyan’s book

- Joyal’s Arithmetic Universes

- Tarski’s undefinability (of arithmetical truth) theorem

- Church’s undecidability theorem

- Look at Ian Chiswell and Wilfrid Hodges’s Mathematical Logic (OUP, 2007: pp.249)

Church thesis

- Non-classical logic

- Priest, G. 2008. An Introduction to Non-Classical Logic: From If to Is, 2nd edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beall, JC, and van Fraassen, B. C. 2003. Possibilities and Paradox, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Modal Logic

- Belnap, N., M. Perloff, and M. Xu, 2001, Facing the Future, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Benthem, J. F. van, 1982, The Logic of Time, Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

- Benthem, J. F. van, 2011, Logical Dynamics of Information and Interaction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Blackburn, P., with M. de Rijke and Y. Venema, 2001, Modal Logic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chalmers, D., 1996, The Conscious Mind, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Goldblatt, R., 1993, Mathematics of Modality, CSLI Lecture Notes #43, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kripke, S., 1963, “Semantical Considerations on Modal Logic,” Acta Philosophica Fennica, 16: 83–94.

- Prior, A. N., 1957, Time and Modality, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Syntax vs semantics The distinction between syntax and semantics is one of the fundamental distinctions in the modern logic. We have to understand the origins of this distinction better. Some have traced it back to Frege. Also see this article by Szabó

- Synthetics vs analtics

- Intensional vs extensional

- Logical vs non-logical

- Logic vs Geometry (sheaves)

The conception and perception of the universal objects in category theory (c.f. Husserl’s ideas on the universal objects)

- Mathematics as a community activity

- decay

- loss of conceptual understanding

- trust is the currency of scientific community

- paradigm shift

- dogmas

- systematization

- Current trends and programmes in mathematics

- The Langlands program

- The synthetic methods (category theory and type theory)

- Non-commutative geometry and topos theory (appropo Riemann Hypothesis)

- P vs NP

- Complexity

- Pyknotic stuff

We shall not cease from exploration And at the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time

Semiotics and Mathematical notations

- Louis H. Kauffman. The Mathematics of Charles Sanders Peirce

- Cajori, F. 1993. A History of Mathematical Notation, New York: Dover Reprints. (Original published in two volumes by Open Court in London in 1929.)

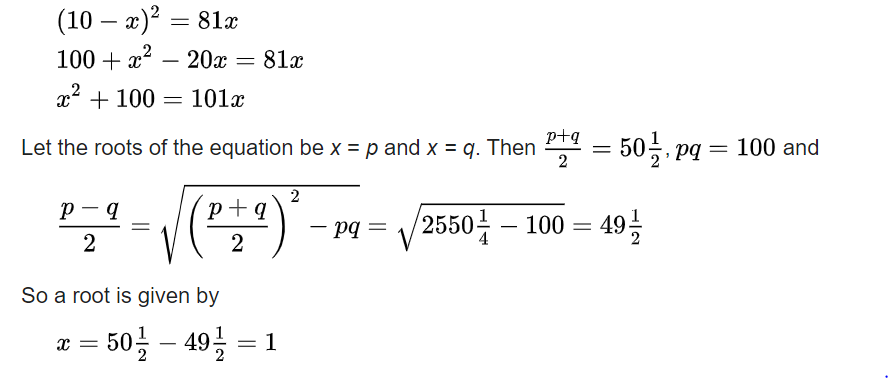

There is a lot to be said about the mathematical notations and symbols: for millenia they have been cognitive technologies enabling us to think previously unthinkable thoughts. For instance, take Khwarizmi’s solution of the problem of solving the quadratic polynomial equation:

If some one says: “You divide ten into two parts: multiply the one by itself; it will be equal to the other taken eighty-one times.” Computation: You say, ten less a thing, multiplied by itself, is a hundred plus a square less twenty things, and this is equal to eighty-one things. Separate the twenty things from a hundred and a square, and add them to eighty-one. It will then be a hundred plus a square, which is equal to a hundred and one roots. Halve the roots; the moiety is fifty and a half. Multiply this by itself, it is two thousand five hundred and fifty and a quarter. Subtract from this one hundred; the remainder is two thousand four hundred and fifty and a quarter. Extract the root from this; it is forty-nine and a half. Subtract this from the moiety of the roots, which is fifty and a half. There remains one, and this is one of the two parts.

And all these words and their meaning are compressed in in modern mathematical notation.

And what if I am interested in set theory?

- very basic intro

- THE FIVE WH’S OF SET THEORY (AND A BIT MORE)

- More resources on awesome-math