Spaces of Being

Published:

I remember when I read Being and Time for the first time, the idea of the Clearing sounded to me like the blank space between characters in a text, or between the notes of a musical score, or the silcence between the notes. Because what’s the significance of the blank spaces between characters? That it makes reading possible at all. The capacity of a communication channel to transimit information is contingent on the absence of noise. And music would not be possible without the silences between the notes. This is also what I understand Plato’s receptacle concept of space of beings Khôra (χώρας). The space is the stage for things to manifest themselves, to be present, to be intelligible.

There is however a very important difference between Plato’s Khôra and Heidegger’s Clearing, and I want to explore this difference in this post.

The Receptacle Concept of Space

In Plato’s cosmologyTimaeus, there is a world of Forms, and, separate and in contrast to this world there is the sensible world of becoming. Plato considers the world of Forms as the world in which everything “always is,” “has no becoming,” and ‘‘does not change’’. For Plato this is the world of beings. In contrast, everything in the world of becoming “comes to be and passes away, but never really is”. This world is grasped by opinions and sense-perception. The name for this world is Cosmos The original meaning of kósmos in Greek was “order, proper order of the world”. It was used by philosophers, such as Pythagoras and Plato, to refer to the universe as an embodiment of order and harmony. It also had a secondary sense of “ornaments of a woman’s dress, decoration”, as well as a religious sense of “worldly life, this world”.

The Cosmos itself came into being, created using as its model the world of Forms. Think of Cosmological entities as imperfect images of the the true and perfect beings in the world of Forms. Mathematical objects, for instance spheres, are forms. But we ever see in this physical world their imperfect shadows. The only way to grasp the form of the spheres is to try to understand it as a mental object through the practice of reflection and introspection. This is mathematics. In Republic, Plato writes that the students of geometry

make use of the visible forms and talk about them, though they are not thinking of them but of those things of which they are a likeness, pursuing their inquiry for the sake of the square as such and the diagonal as such, and not for the sake of the image of it which they draw.Republic 510d

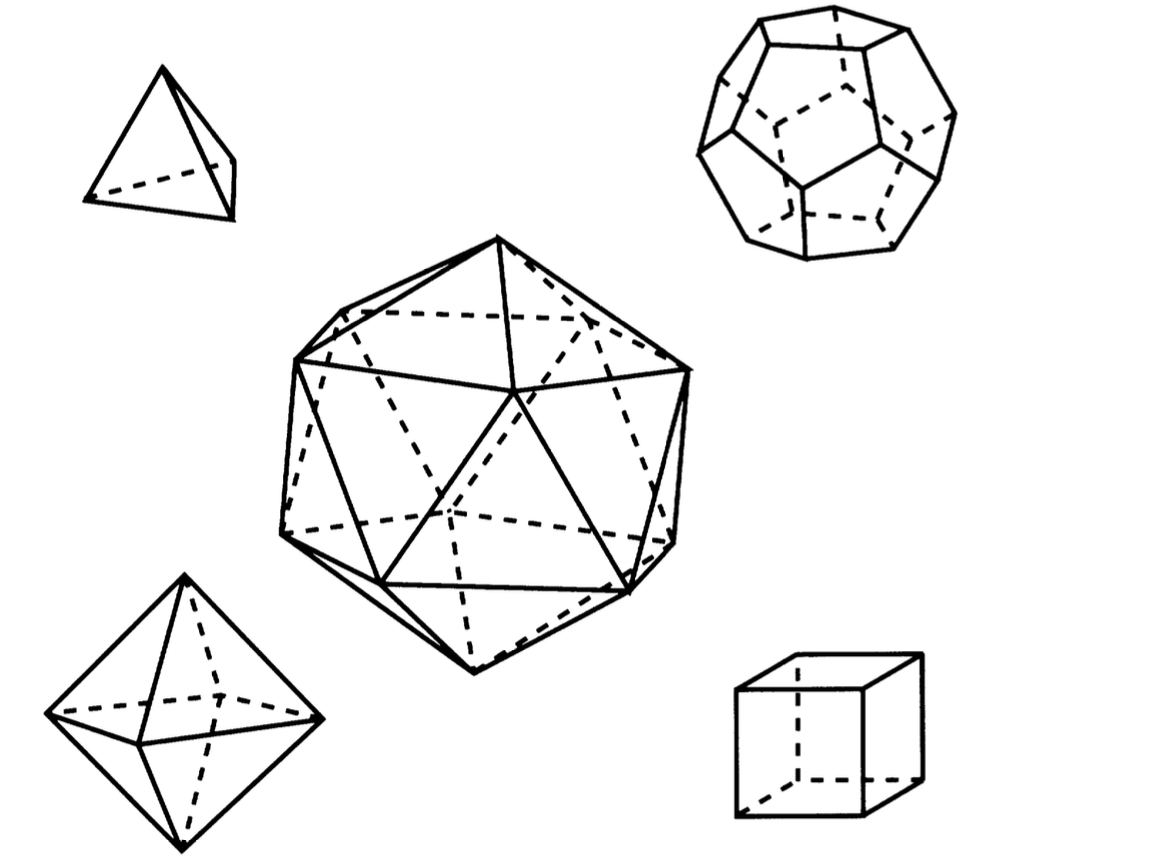

The Pythagorean/Platonic solids

The Pythagorean/Platonic solids

In fact, Plato goes one step further. He theorizes that the whole cosmos is composed of five kinds of regular polyhedra. The cube is associated with earth, the tetrahedron with fire, the octahedron with air, the icosahedron with water and the dodecahedron with the whole cosmos.

This story gets a bit more complicated: There is a third Kind (triton genos) other than the intelligible-sensible dyad, namely khôra (χώρα): It designate a receptacle, a space, a material substratum. It is a formless, invisible, and a passive medium that receives the copies of the eternal Forms from the intelligible realm and shapes them into the sensible world. Khôra is neither being nor non-being, but something in between.

Moreover, a third kind is that of the Khôra (χώρας), everlasting, not admitting destruction, granting an abode to all things having generation, itself to be apprehended with nonsensation, by a sort of bastard reckoning, hardly trustworthy; and looking toward which we dream and affirm that it is necessary that all that is be somewhere in some place and occupy some khôra; and that that which is neither on earth nor anywhere in the heaven is nothing.Plato, Timaeus, 52a-b

There is a way in which one can read khôra as the Primordial Nature existing before the orderly nature of the intelligible, however this reading stretches Plato’s original text.

An opening of light in the Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland, picture by yours truly.

An opening of light in the Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland, picture by yours truly.

Heidegger’s Clearing

Some thinkers have reinterpreted Plato’s receptacle concept of space of beings Khôra (χώρας): Martin Heidegger offers the notion of Clearing. Heidegger’s Clearing (Lichtung) offers a reinterpretation of Khôra: the open space or region where being manifests itself and becomes intelligible to human beings.

In the midst of beings as a whole an open place occurs. There is a clearing, a lighting… Only this clearing grants and guarantees to us humans a passage to those beings that we ourselves are not, and access to the being that we ourselves are.

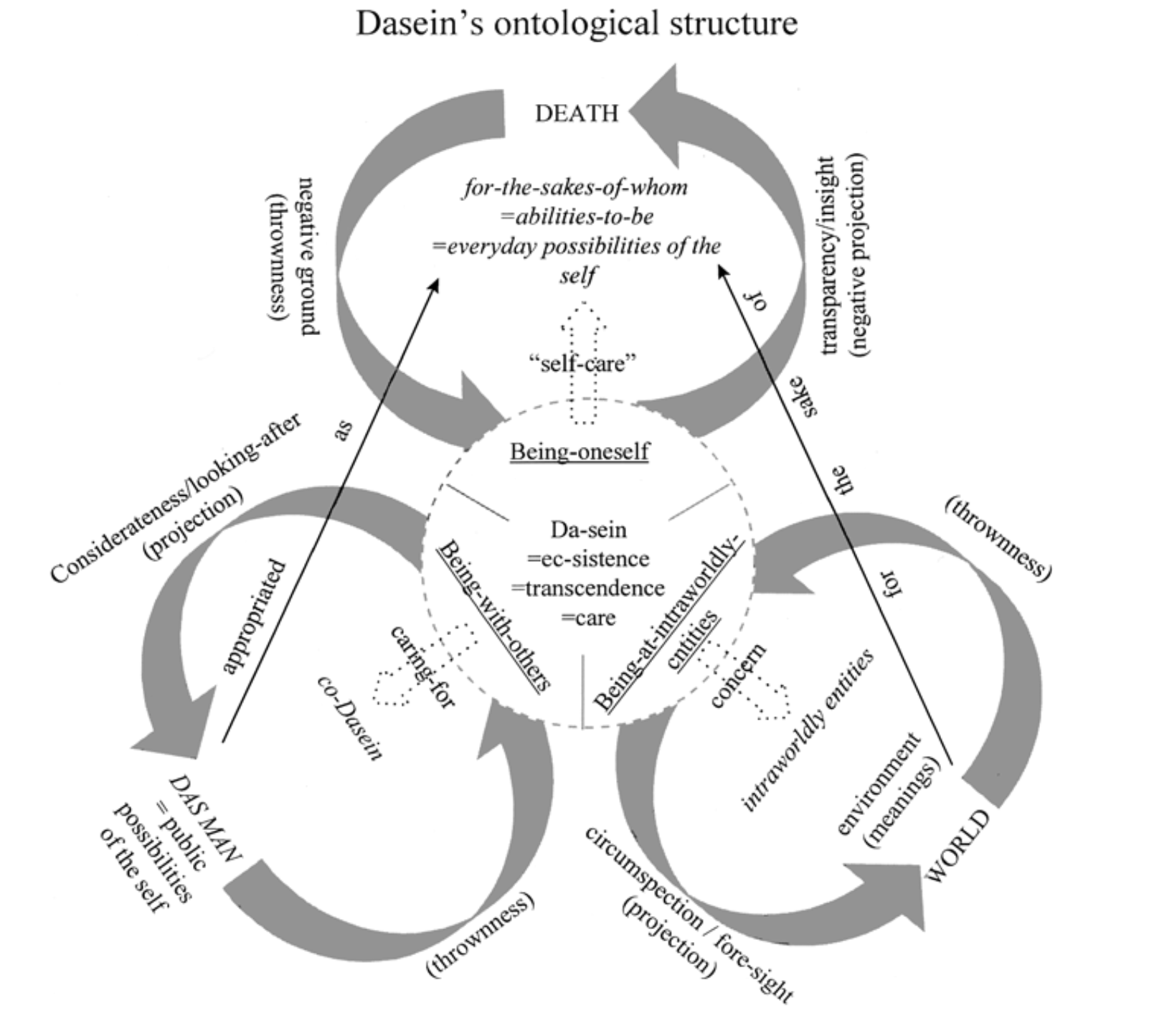

From Edgar C. Boedeker Jr, Individual and Community in Early Heidegger, Inquiry, 44:1, 63-99, 2001.

From Edgar C. Boedeker Jr, Individual and Community in Early Heidegger, Inquiry, 44:1, 63-99, 2001.

In Heidegger’s philosophy, Being can be analyzed into three essential and co-constitutive moments: “encountering” entities, “projection”, and “thrownness”. To interpret an entity as “referring to” a possibility is to seize or grasp (ergreifen) that possibility expressly (eigens). For someone to seize a possibility expressly is thus for her to project an entity upon that possibility. When this occurs, Dasein also allows the entity in question to show itself in terms of, or to be “illuminated” by, the possibility to be actualized in the future. In keeping with the “lighting” function of expressly seized possibilities, Heidegger refers to the totality of meaning-possibilities as a “lighted clearing” (Lichtung) e.g. Sein und Zeit 133 or “the open’ (das Offene).

The Clearing is the site of the event of Ereignis (appropriation), where being reveals itself and claims human beings as its own.

There is however a very important difference between Plato’s Khôra and Heidegger’s Clearing: The former is a receptacle, a container, a space that is passive and inert, whereas the latter is an active and dynamic process of revealing and concealing. Heidegger, as the title of his book (Sein und Zeit) suggests, has temporalized the ecstasis (existence) instead of conceiving it in a spatial sense like Plato did. For him, one main perspective that Dasein related to himself is through the perspective of being-unto-death. This movement unto death is characterized as the ecstatic movement as such, man (a people or a collective ) is situated in history. The historical sitaution of Dasein of our time, according to the post-war Heidegger, is simply the movement of technicity.A first approximation translation of “technicity” is technologization. This means for Heidegger that as partakers in a collective, we are mostly agents of an encompassing technical operation that spans the world as a whole in a technological web to the point that even the frame of mind with which we think about the world around us is technological..

Sloterdijk’s Spaces of Co-existence and Co-immunity

Following the footsteps of Heidegger, in his celebrated magnum opus “Sphären” trilogy, Globen, Peter Sloterdijk uses topology of globes and spheres as the running spatial metaphor for immunity, nurturing, symbiosis, and coexistence. His philosophico-morphological theory is based on an understanding of the history of culture as spatialisations of forms. He blends form, order, and thinking into the mix of spheres and the result is the archaeology of the human attempt to dwell within spaces, from womb to globe.

Throughout the history of philosophy, the receptacle concept of space has in some form or another been dominant such as in Plato or in Aristotle’s concerning world-spheres. Some conceived human existence as the wandering through different receptacles. Humans come out of the first receptacle, the mother’s womb, and they end in a grave, also a receptacle. They go from container to container and in the middle stage of their passage, there is this great container which is the world.

Sloterdijk’s trilogy of spheres is an ambitious and provocative attempt to rethink the receptacle way of thinking about spaces of being. He uses the metaphor of spheres to describe different forms and modes of spatial relations, from the intimate to the global to the plural.

Sloterdijk challenges the modern conception of space as a homogeneous, abstract and neutral container, and proposes instead a dynamic, relational and affective understanding of space as a product of human practices (anthropotechnics) and interactions.

We know and use at least two or three deeply differing concepts of space. One is the concept of space used by physicists, mathematicians or topologists. It is the homogeneous space, the completely neutralized space in which the equipotentiality of points is presupposed as a mathematical axiom, perhaps even as an ontological axiom. Between equipotential points one can draw an arbitrary number of lines, as many times as one would like. This concept of space is mostly used by neo-liberals and also by common commentators when they speak of globalization. They usually mistake this geometrical space of points in topology for the space of geographers. The geographer’s space is a space that already comes closer to reality, to the living space of natural subjects, which understand space to be something like environment (Umwelt). For us that is usually connected to the sense of dwelling, of the space of living. So inasmuch as people are living creatures that dwell, they create a wholly different and living, vital space, a space of meaning, in which all objects around are charged with a variety of semantic values. And then there is a third concept of space, which is in a sense the most mysterious, and which my work actually deals with most – that is, the first part of my trilogy (Sphären) – and that is […] in a sense the ‘psychodynamic space’, which is the space in which existence takes place. […] For me, the relational space of existence is to be understood as ecstatic coexistence in the souls of others, or in the field of the soul of others, and vice versa. They themselves are ecstatic because the other always already penetrates them. And that means somehow that that erotic ecstasis is prior to the subject itself […] when one operates with three so different concepts of space, one needs relatively many words to separate them from each other. The Space of Global Capitalism and its Imaginary Imperialism: An Interview with Peter Sloterdijk.

The secular/global space may be characterized as that which is of neutral value, that which has no innate qualitative differences, and is thus indicative of a chaotic, unstructured level of human experience. Sloterdijk like Heidegger rejects the “cartesian” world-picture whereby it is assumed that we, as the the master manipulator of the world, can take the world apart and divide it up in its components and understand the causal relations between them, in such a way that we instrumentally manipulate the world in whatever way we like. We can remain at the centre of the world and at the same time apart from it, from where we rule the world.

Generated by Bing AI Image Creator

Generated by Bing AI Image Creator

In Sphären Sloterdijk develops a new understanding of modern spaces of coexistence and co-immunity in the wake of death of God. He traces the evolution of his spatial forms from the primal bubbles of intimacy and symbiosis, such as the mother-child dyad, to protective membranes and immune systems, to the globes of imperial and universalist ambitions, such as the Roman Empire, Christianity, and the 20th and 21st century Global Capitalism. Later in the Foams, he considers the fragmented and networked multiplicities, such as the modern metropolis and the internet. Sloterdijk argues that every sphere is a form of immunization, a way of creating a habitable interior within a hostile exterior. In Sloterdijk’s spherology, there are spheres within spheres and spheres over spheres. Like Nietzsche, Sloterdijk criticizes the dominant paradigms of Western philosophy, such as Platonism and Cartesianism, for their dualistic and transcendental tendencies that separate humans from their worldly conditions.

The true world – we have abolished. What world has remained? The apparent one perhaps? But no! With the true world we have also abolished the apparent one. [...] I conjure you, my brethren, remain true to the earth, and believe not those who speak unto you of superearthly hopes!

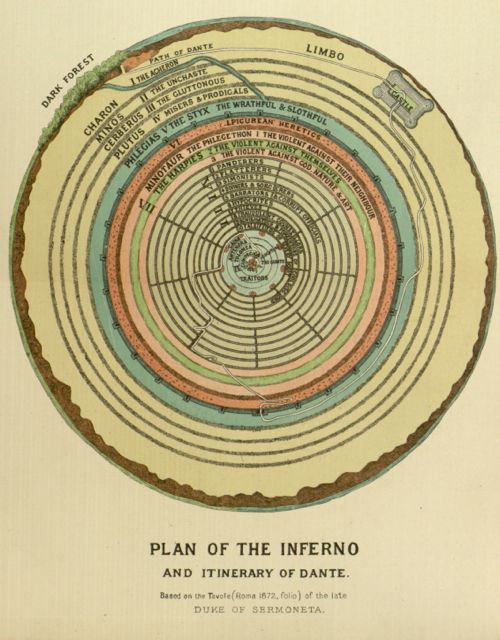

Dante's circles of Hell.

Dante's circles of Hell.