AI and Mathematics

Published:

warning: The article below is incomplete and is under construction! Please refer to the pdf file above for the full details.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to explore and report on the state-of-the-art in machine learning (ML) for mathematical research, serving as an extension to Williamson’s survey 1. Our main contribution is the impact of LLMs and recent advances in the theorem-proving community.

Mathematics, as a societal endeavor, encompasses teaching, learning, research, publishing, and outreach. There are complex dynamics between different stakeholders. Corporate interests often diverge from academic research.

Academic research itself is bounded by exhaustive publication protocols. The social nature of Mathematics often transcends beyond private thoughts, and its utility can raise crucial ethical questions 2. However, due to constraints, we curtail our discussion here. We refer to the text 3 for an introduction to these ideas.

The structure of the article follows that of a research mathematician, as described by Atyiah 4

In mathematics, ideas and concepts come first, then come questions and problems. At this stage the search for solutions begins, one looks for a method or strategy…Before long you may realize, perhaps by finding counterexamples, that the problem was incorrectly formulated… Without proof the program remains incomplete, but without the imaginative input it never gets started.

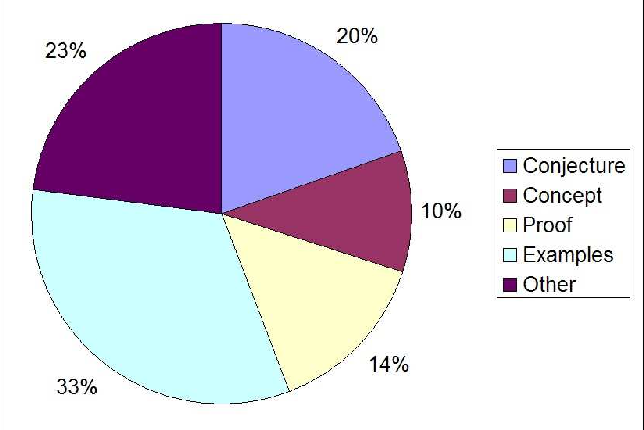

This distribution of mental activity is partly reflected in the survey of an online collaborative project 5, see the figure below.

In section on abductive reasoning, we discuss progress towards the first stages of conjecturing. In the section on deductive reasoning, we discuss progress towards AI-assisted proofs, or formalization. Lastly, in the section on future directions, we outline recent attempts in which the two are integrated. As observed by many (see e.g. 6) AI-enabled mathematics not only helps mathematicians in their research but also serves as a litmus test for AGI itself: the ability to reason mathematically is a central unsolved problem in artificial intelligence.

Language Models for Mathematics

Recent advances and successes of large language models suggest an exciting avenue. Modern LLMs are based on the decoder transformer architecture 7. With transfer learning, one can leverage the pre-trained model’s knowledge to achieve better performance on the target task, even with limited labeled data.8 This led to a range of pre-trained language models on mathematical data and fine-tuned on mathematical tasks.

Language models satisfy the following two important properties:

- Scaling laws: The ability of the model scales with both the number of parameters and the training corpus. The availability of good quality training corpus compared to natural language is scarce. In terms of training corpus, there are generally two types:

- In-context learning (a.k.a prompting): This is a surprisingly simple way that steers LMs. This is the process of augmenting the context of instruction.

The extent to which mathematicians can leverage language models will be the focal point of this survey paper. 10

Both humans and AI need to develop skills to analyze this new type of text. The stylistic signals that I traditionally rely on to “smell out” a hopelessly incorrect math argument are of little use with LLM-generated mathematics. Only line-by-line reading can discern if there is any substance. Strangely, even nonsensical LLM-generated math often references relevant concepts. With effort, human experts can modify ideas that do not work as presented into a correct and original argument. 11

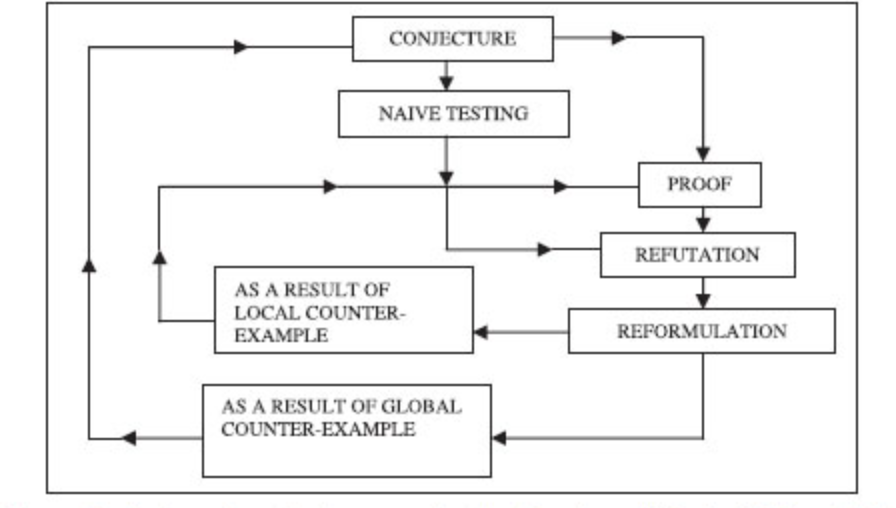

Learning from Lakotos: Conjectures and counterexamples

In the enlightening book, Proofs and Refutations of Lakatos 12, Lakatos imagines an imaginary classroom, where the teacher makes a conjecture of the Euler-Poincaré formula for polyhedra: given a polyhedron where $V$, $E$, and $F$ are the number of vertices, edges, and faces, respectively, then

\[V - E + F = 2\]The teacher provides an attempted proof where students respond by providing counterexamples. The dialogue continues back and forth, and the process can be summarized as

The two key elements are generating conjecture (see Section Generating New Concepts) and verifying conjecture (see Section Conjecture Verification). This section explores how AI can assist in these two parts. Lastly, we note that there are fields of machine learning which have a direct and immediate impact on all natural sciences, such as semantic search - once a conjecture is made, the first step would often be a search on whether similar results have been proven. For instance, a typical query would be of the form: “Is it true that $X$ is satisfied for $Y$?”. Such open-ended questions are hard. It is also unlikely that the same phrasing or even words were used in the hypothetical reference. We limit our discussion to aspects of ML methods that are particular to the field of mathematics.

Generating conjectures and new concepts

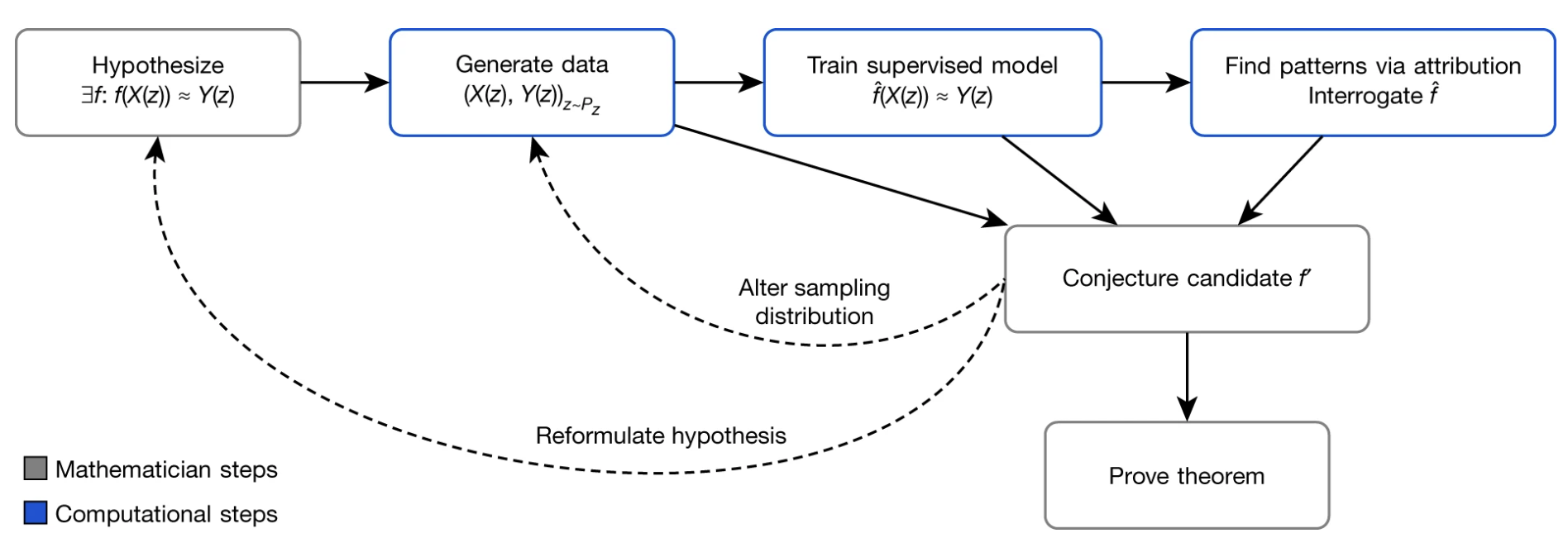

One of the more prominent approaches to generate hypothesis follows the pipeline of Davies et al.12

To illustrate this, consider the example of the Euler-Poincar'e formula. One begins at the leftmost blue box. The grey boxes are required by human intervention. One conjectures a relation between features $X(z)$ and $Y(z)$ of a polyhedra $z$. In our case, we let

\[X(z)=(V(z), E(z), \text{Vol}(z), \text{Sur}(z))\]be the number of vertices, edges, volume, and surface area of $z$, respectively. Let

\[Y(z)= F(z)\]be the number of faces of $z$. Our goal is to find a function $\hat{f}(X(z))=Y(z)$. Using classical supervised learning, we can obtain

\[\hat{f}(X(z))=X(z) \cdot (1,-1, 0, 0)+2\]However, when data is high dimensional and the underlying relation is non-linear, $\hat{f}$ is only there for intuition. The outcome of this training process is thus accompanied with attribution techniques, such as gradient-based techniques 13. Another related work is the Ramanujan14 machine. The machine attempts to find equality of the following form:

\[x = a_0 + \frac{b_1}{a_1 + \frac{b_2}{a_2 + \cdots}} \quad a_n, b_n \in \mathbb{Z}\]One often refers to the right-hand side as polynomial continued fractions (PCFs). For example, the Golden ratio can be represented as:

\[1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \cdots}}\]The Ramanujan machine algorithm produced several new equalities, and new conjectures. The approach is to define a space of meaningful PCFs and reduce the problem to a search problem. There were two search algorithms suggested: one referred to as Meet-In-The-Middle, and the other is gradient descent, which is the same as that used in machine learning. An interesting step forward, as suggested in 15, is whether one can more effectively create this space by using recent advances in NLP, via finding latent representations from widely available scientific corpus. This was used in the context of chemistry 15.

Another key aspect of mathematics is creating definitions 7. Two recent example of the importance of creation of a good definition to advance mathematics are the notion of quasicategories 16 and perfectoid spaces 17. We end this subsection with the open question: could AI create new meaningful and useful definitions?

Williamson, J. Is deep learning a useful tool for the pure mathematician? ArXiv, 2023 ↩

Maurice Chiodo and Toby Clifton. The importance of ethics in mathematics. European Mathematical Society Magazine, (114):34–37, 2019. ↩

Reuben Hersh. What is mathematics, really? Mitteilungen der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung, 6(2):13–14, 1998. ↩

Timothy Gowers, June Barrow-Green, and Imre Leader. Advice to a young mathematician. 2010. ↩

Alison Pease and Ursula Martin. Seventy four minutes of mathematics: An analysis of the third Mini-Polymath project. 2012 ↩

Yuhuai Wu et al. Autoformalization with Large Language Models. 2022. ↩ ↩2

Note, however, that the inference of what a model makes is often dependent on its training corpus. ↩

Dan Hendrycks et al. Measuring Mathematical Problem Solving Difficulty. 2021. ↩

We do not discuss on the fundamental problem of LLM’s availability and their monetary restrictions. This, however, has immediate consequences for researchers. Smaller models empirically exhibit poorer estimation of tails of distributions, places higher probability mass on repetitions, etc, many of such empirically do not appear in larger models ↩

Tao, T. (2023). Summary of the current state of the art in using LLM-generated materials. ↩

Davies, A., et al. (2021). Advancing mathematics by guiding human intuition with AI. Nature, 600(7887), 70-74. Link ↩ ↩2

Sundararajan, M., Taly, A., & Yan, Q. (2017). Axiomatic Attribution for Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (Vol. 70, pp. 3319-3328). JMLR.org. Link ↩

Gal Raayoni, et al. Generating conjectures on fundamental constants with the ramanujan machine. Nature, 590(7844):67–73, feb 2021 ↩

Tshitoyan, V., et al. (2019). Unsupervised word embeddings capture latent knowledge from materials science literature. Nature, 571(7763), 95-98. Link ↩ ↩2

Leave a Comment